A Palestinian Family’s History—Told Through Olive Trees

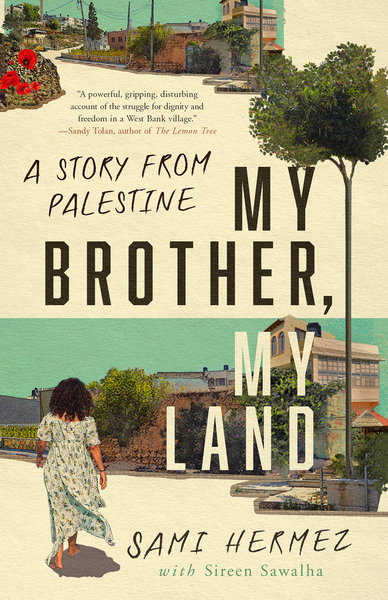

Excerpted from My Brother, My Land: A Story from Palestine by Sami Hermez with Sireen Sawalha. Published by Redwood Press, an imprint of Stanford University Press, ©2024 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

Sireen Sawalha was born in Kufr Ra’i, a village in the West Bank, in 1966. The next year, the Israeli military attacked Egypt and set off a Six-Day War with its Arab neighbors (including Syria, Jordan, and Iraq) that ended with Israeli forces occupying the Syrian Golan Heights, Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, and all of historic Palestine, including the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. For his book My Brother, My Land, anthropologist Sami Hermez conducted research for over a decade and interviewed Sawalha extensively so he could chronicle the following decades of her family’s life under Israeli occupation.

From tending the land where olive trees grow to the story of how Sawalha’s younger brother, Iyad, became involved in the Palestinian armed resistance movement, the story weaves together oral history and memoir to present a resolute and layered account of a people longing for equality and freedom. The book often tells the story in Sawalha’s own words, centering her voice and giving her the authority to shape the text with Hermez. Ultimately, as Hermez told me, the collaboration resulted in a form of creative nonfiction “meant to move readers as it tells the story of Palestinians living under occupation.”

In the excerpt below, Sawalha recalls the rituals of the olive harvest season, which shaped much of her life growing up in the West Bank in the 1960s and ’70s. Olive trees continue to provide an essential source of income for tens of thousands of Palestinians and remain a resonant symbol of their resilience and right to self-determination. Israeli military forces and Zionist settlers have long targeted Palestinian olive trees for these reasons, from beating and attacking farmers during harvest season to uprooting approximately 1,000,000 olive trees since 1967.

These systemic efforts to destroy Palestinians’ access to their olive trees have only intensified since October 7, 2023. Israeli forces and settlers in the West Bank have burned trees and banned farmers from accessing their agricultural lands under threat of death. As Israeli forces continue to bombard Gaza today, olive trees are among the precious casualties of war. Satellite images from March 21 of this year show the staggering scale of damage to Gaza’s land from the direct and collateral damage of Israel’s onslaught: almost 50 percent of all tree cover destroyed since October 7; fields and orchards razed to desert; air, soil, and water contaminated.

Sawalha’s detailed account of her family’s harvest time, read against this background, crystallizes what is lost when the olive trees are lost: entire networks of relationships, ways of marking time, and ancestral knowledges of place. In other words: an entire world. But she also makes clear that the trees’ roots, and the ties to the land that Palestinian people have maintained over centuries, remain deep and steady despite these attempts at their erasure.

—Emily Sekine, SAPIENS Editor

Sami Hermez:

If Palestinians did not measure time through migration and the moon, if they had not adopted the Gregorian calendar with Aramaic rhythms, the olive harvest would surely mark the new year. It was, in any case, a festive season.

In the fall harvests of Sireen’s youth, children in the village tried to evade farmers so as to steal olives and sell them for pocket money. They ditched school or went to the olive groves immediately after class in small groups. Knowing this, Um Yousef (Sireen’s mother) forced her children to head to their land right after school to watch over the few olive trees the family owned.

Sireen Sawalha:

During the olive harvest, my mother chose two of the three of us eldest girls to go help while the third stayed home with our younger siblings. Each day, we were told who was going and who was staying. We took our schoolbooks to the olive grove and waited till sunset. The minute we heard the call to Maghreb prayer, we were allowed to return. We were sent without food, so we went hungry till prayer time. My mother didn’t give us any money to buy sandwiches, bread, or cookies from the school canteen either. I remember those days, too hungry to focus on our homework. This was the routine for the latter part of September and sometimes into October.

My father had a plot of land in the valley, el-wad, and another on a rocky hill near town where the olive trees grew. This land was called the hawacheer for its flat terraces. To get to the hawacheer, we had to cross through the village and then make our way down to the land from a back road. When it was time to harvest olives, Suzanne, Maysoun, and I went with our mother, who, unlike almost everyone else in the village, never hired anyone outside the family to help with the harvest. When we were older and busier, she finally hired our neighbor, Um Khaled, to help her.

On school days, we would all return home, the boys and girls, change out of our uniforms, and follow our mother to the hawacheer. When my brothers were a little older, though, they preferred to spend their time in more exciting ways, with boys in the village planning to resist the Israelis or talking about who in town was collaborating with the enemy and what to do with them.

In the grove, my mother would spread large, thick plastic sheets under an olive tree. One of us would climb up a ladder and pick the olives off their resilient branches, then we would drop them to the ground. Other farmers beat their branches, but my mother banned that type of practice on her trees. She taught us that handpicking olives preserved the younger boughs that produced olives the following year.

Aside from these differences in how to pick the olives, my mother followed the conventional methods of our village for their preparation. Once we returned home, she divided the olives for pickling. She prepared one half by pounding them—the madqouq—and the other half by slicing them—the mshatab. For the madqouq, we took each olive and smacked it with the old wooden garlic beater. For the mshatab, we took each one and sliced the top in quarters. It took forever.

My mother then stored them separately. The madqouq didn’t last as long, she would say. The salt and water would seep in and rot them faster than the mshatab.

The olives were too bitter to eat if they didn’t undergo a specific preparation. My mother submerged them in salt and water every day for a week. Each day, she switched out the saltwater until the bitterness faded. After that, we put the olives in a container with lemon and hot peppers, sealed them, and waited three weeks before tasting them. The batch we made in October lasted us the whole year.

We sent the remaining olives that weren’t pickled to be pressed into olive oil. Back in the 1970s, we had two olive presses in our village. People from other villages, and even from cities such as Nablus, Jenin, and Tulkarem, came to Kufr Ra’i to use them to press their olives.

My maternal grandfather, Sidi Haj Sadeq, had one. His son had sent it to him from Germany in the 1970s. There was also an older one in the village made of two large stones on which the olives were placed and then pressed. But Sidi’s was new, made of steel, and powered by hydraulic pressure. I remember the basin of water used to operate the engines was filled with frogs and terrified us as kids.

When I was young, I often went to Sidi’s house, grabbed hot bread from the taboon, dipped it in freshly pressed oil, sprinkled salt on it, and ate it. The oil would still be hot and slightly bitter.

Sidi’s press still operates today.

I remember his house vividly. It was one of the largest in the area around Jenin. It was built with granite and had a spacious yard. The gate into the grounds had multiple openings—for people, for cars, and even one for a truck. Guests parked in a large space near a guesthouse separate from the main house.

Iyad and I played hide-and-seek in that big house. Iyad was so skilled at locating the best hiding places and squeezing into tiny nooks. Sometimes, I couldn’t find him and had to give up.

I remember one time I tripped while looking for him, hurt my knee, and cried. Iyad heard me and instantly jumped out of his hiding place, worried about me. I was fine, but he remained concerned and gave me a hug. Iyad worried about us a lot, even when he grew older. Later when he became a resistance fighter, the Israelis used this against him.

In the winter, Sidi would sit in one of the rooms that had an Arabic seating arrangement—mattresses and cushions laid out against the walls—and feed us the tastiest chestnuts cooked on a qanun, a brass fireplace.

Sidi used to spoil me with things. He once bought me a pink outfit that I still remember because I have pictures of myself wearing it with a boyish haircut that was my style in those years. He’d frequently take me on trips to Jenin, where he’d buy me new clothes, or to Nablus, where he’d get me jewelry from a shop called Shahrazad. And most of all, I remember he’d give me raha—Turkish delight—with two biscuits that I ate like a sandwich, something my mother never gave us.

In the fall, my grandparents would lay out 20–30 mattresses on the ground of the guesthouse to accommodate the people who came from around the areas of Jenin, Nablus, and Tulkarem to press olives. They arrived on horse and pushcart, and they sometimes had to wait two to three days to have a turn with the olive press before leaving.

My grandmother, Siti, prepared breakfast, lunch, and dinner. She made phyllo dough, kneading it until she produced fine layers that guests ate with sugar or honey. A Druze man we knew well would bring honey from his village near Nazareth in exchange for oil, so they had a lot of honey that the guests loved. Sidi never took money for the use of the press in all those years. He just asked for payment in oil from what users produced.

At Sidi’s house, men sat together during the day, sipping tea, smoking cigarettes, and arguing about politics. They were dressed in their kumbaz, long, loose gowns of various colors, but mostly white, blue, black, or brown. Over the kumbaz, they wore suit jackets. Sidi almost always wore a men’s copper-brown abaya over that. On their heads, they wore plain white kaffiyehs or checkered red-and-white or black-and-white ones that are a symbol of Palestinian resistance. They sat on hard, colorful, embroidered cushions, their feet bare, laughing, relaxing, some even taking midday naps. In another corner, close enough for the men and women to hear one another, women also shared cups of tea, talking about the harvest but also debating politics. They wore colorful abaya—black robes with green-and-red tatreez embroidery from the outskirts of Nablus or white robes embroidered with pastel blues or yellows from villages around Jenin. I also remember how the children ran around, lay in their parent’s laps, and, on occasion, got into trouble. At night, the air was filled with poetry, with music, and always with stories that visitors brought with them from near and far.

It really was a festive time.

Sidi owned much land around Kufr Ra’i, much of it planted with olive trees. He would bring 30–40 people to harvest the olives during this season. He was like a feudal lord, the wealthiest man in the village. Much of the olive oil sat in beautiful, colored-glass bottles set on straw in a warehouse and around the grounds of his house. It was traded locally, but in the 1960s and ’70s, he started to export the oil to Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Abu Dhabi, and Jordan. As wealthy as he was, he never wanted his children to depend on him, so my mother did not see any of the money. He gave much to charity or to build schools, but to his children, he rarely gave anything. He offered to paint our house, pay the tiller to till our land, or help my mother improve our place. He gave us olive oil if our trees did not yield enough fruit. But rarely did he give money, as he did not want my father to get lazy and rely on him.

Sami Hermez:

Though the olive season was so central to their lives, Um Yousef only had around 11 trees in Sireen’s youth, and it was only later that her family began to grow more of them, after many seasons of Sireen’s life had passed and she had left Palestine.

When she returns, she always maintains a relation with one Roman-era tree. It is the tree she used to climb in her youth, on whose branches she would rest and, from her perch, look out into the vast fields. Now in her middle age, she climbs it as if she were 15, as if she has reconnected with a childhood friend. And when she lies on its branches, the two seem beautifully entangled.

The tree and the land are no longer as secluded as they once were. A road runs nearby; one can see new houses in the vicinity. Sireen looks on at the olive tree and reflects on this spirit living through a long-troubled history, with its crinkled trunk rooted in the soil and long, winding branches pointed to the sky. She cannot help but think of all the other trees the Israelis have yanked from the earth to confiscate Palestinian land and of all the farmers who remain stubbornly faithful to this land that they have cultivated for centuries.